- Published on

Java Virtual Threads: A Practical Overview

- Authors

- Name

- Huan Zhang

- @zhkrob

Background

Recently, I upgraded one of our backend services from Java 17 to Java 21. Since this was a greenfield project built from scratch, I wanted to leverage the latest LTS features.

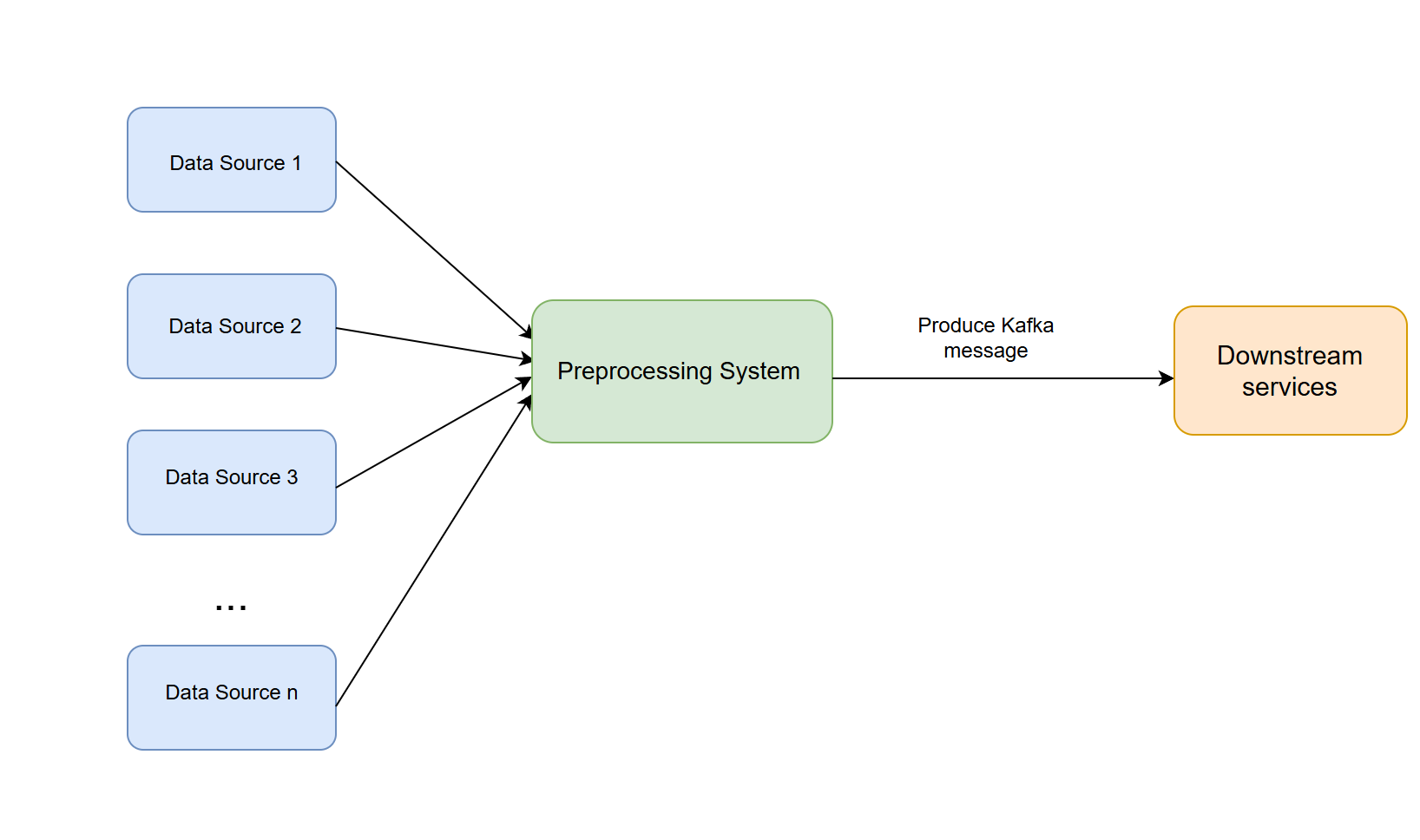

The project is a data pipeline system designed to fetch data from various sources and push it to downstream services via Kafka. The architecture is straightforward:

I encountered a significant bottleneck: some data sources provide large files. Processing these files sequentially was too slow, but spinning up a new platform thread for every row or chunk consumed too much memory.

It was a classic I/O-intensive scenario. My initial thought was to tune the thread pool, but that always involves a tradeoff between context-switching overhead and memory consumption. That's when Virtual Threads (Project Loom) came to mind. I decided to dive deep, research the implementation, and apply it to our pipeline.

Here is my understanding of Virtual Threads, blending practical usage with internal mechanics.

What are Virtual Threads?

Virtual threads were introduced as a preview feature in Java 19 and became official in Java 21.

Let's look at how Java handled concurrency historically.

The "Old" Way: Platform Threads

Classically, a java.lang.Thread is a Platform Thread. It is a thin wrapper around an operating system (OS) kernel thread.

- Mapping: 1 Java Thread = 1 OS Thread (1:1 mapping).

- Cost: Expensive. They carry a large stack (megabytes) and require OS-level context switching.

- Limitation: You cannot create millions of them. The OS will run out of resources.

The "New" Way: Virtual Threads

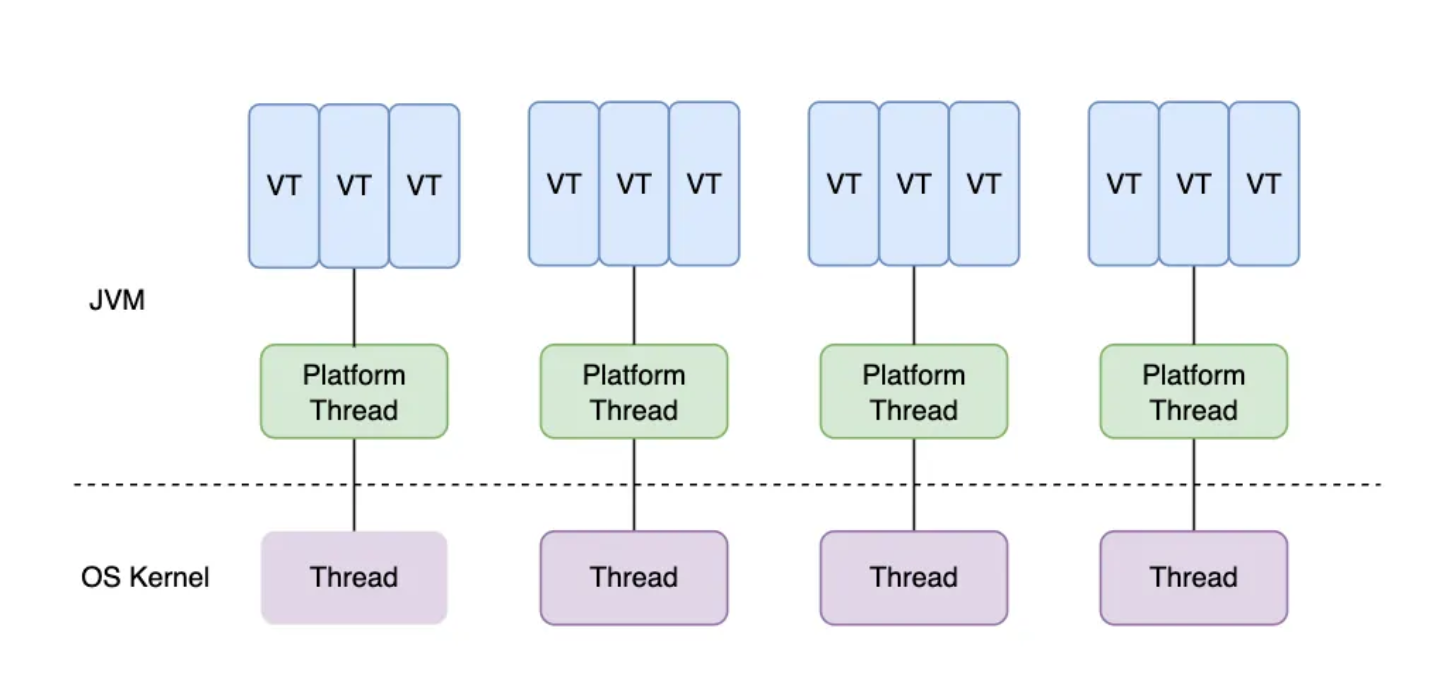

Virtual Threads are lightweight instances of java.lang.Thread that are not permanently bound to a specific OS thread.

- Mapping: Many Virtual Threads share a few OS Threads (M:N mapping).

- Cost: Cheap. They have dynamic, heap-allocated stacks that grow and shrink.

- Scale: You can create millions of them.

When a virtual thread blocks on I/O (like reading a CSV or a network call), the JVM "unmounts" it from the OS thread, allowing the OS thread to do other work.

Virtual Threads vs. Coroutines

It sounds similar to Coroutines in Kotlin or Go, and conceptually it is. However, the key difference lies in the programming model:

- Coroutines (Kotlin/JS): Often require

async/awaitkeywords, explicit suspension points, or "colored functions" (sync vs async). - Virtual Threads (Java): No code change required. You write standard, blocking synchronous code. The JVM handles the suspension magic transparently.

Why Virtual Threads?

1. The "Code Like It's 1999" Simplicity

The biggest benefit isn't just performance—it's readability. We can write simple, sequential code that scales like complex asynchronous code.

The Reactive/Async Way (CompletableFuture Hell):

// Hard to debug, hard to read, stack traces are useless

List<CompletableFuture<String>> futures = urls.stream()

.map(url -> CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

try {

return httpClient.send(url).body();

} catch (Exception e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}, executorService))

.toList();

CompletableFuture.allOf(futures.toArray(new CompletableFuture[0]))

.thenApply(v -> futures.stream()

.map(CompletableFuture::join)

.toList())

.join();

The Virtual Thread Way:

// Looks like simple blocking code, but scales massively

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

List<Future<String>> results = new ArrayList<>();

for (String url : urls) {

results.add(executor.submit(() ->

httpClient.send(url).body() // The JVM handles the blocking!

));

}

List<String> responses = results.stream()

.map(f -> {

try { return f.get(); }

catch (Exception e) { throw new RuntimeException(e); }

})

.toList();

}

2. Efficient Resource Utilization

Because the JVM automatically unmounts virtual threads when they block, we don't block the precious OS threads. This is perfect for our CSV processing pipeline where we spend a lot of time waiting for I/O (reading files, waiting for Kafka acknowledgments).

Under the Hood: How JDK Implements It

At the implementation level, a virtual thread is essentially:

A Thread subclass + A Continuation (Stack) + A Scheduler

I dug into the JDK source code to understand how this magic happens.

1. Continuations: Capturing the Stack

Internally, each virtual thread owns a Continuation object. Unlike a platform thread which has a monolithic block of memory, a virtual thread's stack is stored in the Heap.

When a task pauses (blocks), the JVM copies the stack frames from the carrier thread into this heap object. When it resumes, it copies them back. This is what allows them to be so lightweight.

2. The Scheduler (Carrier Threads)

Virtual threads don't talk to the OS scheduler directly. Instead, Java uses a ForkJoinPool as a dedicated scheduler. The threads in this pool are called Carrier Threads.

The scheduling loop looks roughly like this:

- Mount: The scheduler picks a virtual thread and "mounts" it onto a Carrier Thread (OS thread).

- Run: The code executes until it hits a blocking call (e.g.,

InputStream.read()). - Unmount: The virtual thread yields. Its stack is saved to the heap. The Carrier Thread is now free to take another virtual thread.

- Resume: When the I/O completes, the OS signals the JVM, and the virtual thread is scheduled to run again (potentially on a different Carrier Thread).

This allows a small number of Carrier Threads (usually equal to the number of CPU cores) to juggle millions of Virtual Threads.

Here is a snippet from the JDK (simplified) showing the structure:

final class VirtualThread extends BaseVirtualThread {

private static final ForkJoinPool defaultScheduler = createDefaultScheduler();

private final Executor scheduler;

private final Continuation continuation;

private final Runnable runContinuation;

VirtualThread(Executor scheduler, String name, int flags, Runnable task) {

super(name, flags, /* bound = */ false);

this.scheduler = scheduler;

this.continuation = new VThreadContinuation(this, task);

}

}

3. The "Pinning" Problem

While powerful, Virtual Threads aren't magic bullets. There is a specific limitation called Pinning.

A virtual thread is "pinned" to its carrier thread if:

- It is running inside a

synchronizedblock or method. - It is executing a native method (JNI).

When pinned, if the code blocks on I/O, it cannot unmount. It holds onto the OS thread, blocking it just like the old days.

Advice: In modern Java (with Virtual Threads), prefer ReentrantLock over synchronized blocks if you expect I/O operations inside the lock. Although JEP 491 is working on fixing the synchronized pinning issue, it's good practice to be aware of it for high-throughput systems.

How to Use virtual thread?

1. Simple Usage: The Executor

The easiest way to start is using Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor().

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

IntStream.range(0, 10_000).forEach(i -> {

executor.submit(() -> {

Thread.sleep(Duration.ofSeconds(1));

return i;

});

});

} // Implicitly waits for all 10,000 threads to finish here

2. Spring Boot Integration

If you are using Spring Boot 3.2+, it's literally one line of configuration:

spring.threads.virtual.enabled=true

That's it. Tomcat and Jetty will now use virtual threads for request handling.

Some thoughts on virtual thread

1. Do not pool Virtual Threads

This is the hardest habit to break. With platform threads, we used pools (like Executors.newFixedThreadPool(10)) because threads were expensive resources that needed to be managed and reused.

With Virtual Threads, threads are not resources; they are tasks. The number of virtual threads should always equal the number of concurrent tasks in your application. Converting platform threads to virtual threads yields little benefit. Instead, you should convert tasks to virtual threads.

Anti-Pattern:

ExecutorService sharedPool = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor();

Future<Result> f = sharedPool.submit(task);

Best Practice: Use the Structured Concurrency pattern with try-with-resources. The executor itself is lightweight. Creating a new executor for a logical group of tasks allows the close() method to implicitly wait for all tasks to finish, preventing "thread leaks" and simplifying error handling.

try (var executor = Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor()) {

Future<Result> f1 = executor.submit(task1);

Future<Result> f2 = executor.submit(task2);

}

2. "Throughput" vs. "Latency"

Does a virtual thread make a single request faster? No. A single task running on a virtual thread is not faster than on a platform thread (in fact, it might be infinitesimally slower due to mounting overhead).

The gain is in Throughput. If your server can handle 1,000 concurrent requests with platform threads before crashing, it might handle 100,000 with virtual threads.

3. The "10,000 Threads" Rule of Thumb?

As official document says: "If you don't need 10,000 concurrent threads, you don't need Virtual Threads."

I am a bit disagree on this. While it's true that the raw performance benefits (throughput) are negligible below this scale, there is another critical factor: Maintainability.

Even for smaller applications, Virtual Threads allow you to write simple, synchronous-style code that is easier to read, debug, and test than Reactive or Async code (e.g., CompletableFuture or WebFlux). You get the simplicity of "One Thread Per Request" without the guilt of wasting OS resources.

So, use them not just for scale, but for sanity.

4. Thread Safety still matters

Virtual threads are essentially java.lang.Thread instances and adhere to the same Java Memory Model (JMM) as platform threads. This means:

- No Automatic Thread Safety: Virtual threads are not "safer" than platform threads. Data races, visibility issues, and instruction reordering still exist.

- Same Tools:

synchronized,ReentrantLock,AtomicInteger, andConcurrentHashMapwork exactly the same way.

However, virtual threads can amplify existing bugs due to scale:

- The Scale Problem: In the past, you might have had 500 threads. A rare race condition might happen once a month. Now, with 100,000 virtual threads, that same race condition could happen every second.

- The Pinning Problem (Locks): Using blocking synchronization (like

synchronized) can "pin" the virtual thread to its carrier, preventing it from unmounting during I/O. While this doesn't break correctness, it kills the throughput benefits. UseReentrantLockor non-blocking structures where possible.

5. Use Semaphores to limit Concurrency

Sometimes you need to limit concurrency not to save resources, but to protect downstream services (e.g., rate-limiting a 3rd party API to 10 concurrent requests).

In the platform thread era, we often abused thread pools for this:

// OLD WAY: Abusing thread pool for rate limiting

ExecutorService rateLimitedPool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(10);

rateLimitedPool.submit(() -> callExternalService());

This works, but it conflates "resource management" (pooling scarce threads) with "flow control".

With Virtual Threads, since we shouldn't pool them, we use the tool designed specifically for flow control: java.util.concurrent.Semaphore.

Semaphore semaphore = new Semaphore(10);

void process() {

try {

semaphore.acquire(); // Blocks the virtual thread

callExternalService();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

} finally {

semaphore.release();

}

}

Under the hood, blocking on a Semaphore allows the virtual thread to unmount, just like blocking on I/O. It creates a queue of blocked tasks, which is conceptually identical to a Thread Pool's task queue, but without the overhead of managing a pool of heavy worker threads.

Note on DB Pools: Database connection pools (like HikariCP) act as implicit semaphores. If you have a pool of 10 DB connections, the 11th virtual thread will simply block waiting for a connection. You don't need an extra semaphore there.

Conclusion

If you are building I/O-heavy applications (web servers, data pipelines) in Java 21+, Virtual Threads should be a good choice in most cases.